Efecto de la temperatura y la escarificación sobre la germinación de Ischaemum rugosum Salisb.

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v31i2.38417Palabras clave:

malezas, dormancia, semillas, almacenamiento, cámara de germinaciónResumen

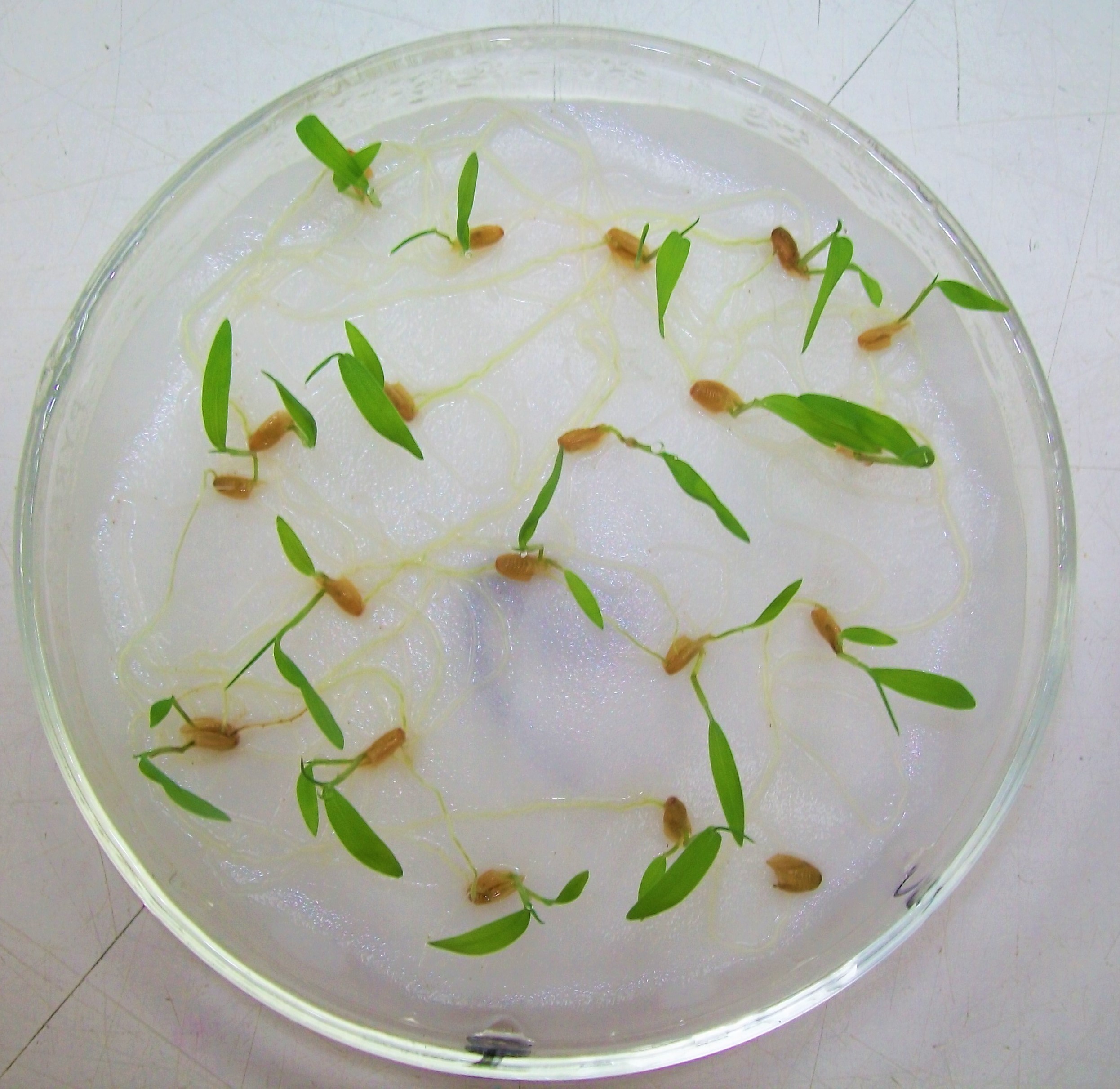

Introducción. La ruptura de latencia de Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. es un aspecto crítico de su fisiología, por lo que su conocimiento resulta indispensable para establecer medidas acertadas acerca de su manejo. Objetivo. Determinar si la temperatura de almacenamiento y la escarificación influyen en la germinación de I. rugosum Salisb bajo condiciones controladas. Materiales y métodos. El trabajo se realizó en octubre del 2015, en la Estación Experimental Fabio Baudrit Moreno y en el Laboratorio Oficial de Análisis de Calidad de Semillas, ambos de la Universidad de Costa Rica. Se evaluó el efecto de la escarificación (semillas con glumas y semillas sin glumas), la temperatura de almacenamiento de la semilla (refrigerada a 5 °C y temperatura ambiente 23,9 °C) y la temperatura en la cámara de germinación (27 °C y 30 °C). Se contabilizaron las semillas germinadas para cada tratamiento. Resultados. Las interacciones dobles fueron significativas. La semilla almacenada a temperatura ambiente tuvo la ventaja de mayor germinación sobre la semilla no escarificada (2,35 a 1), y en este tipo de semilla la germinación se dio por igual en las dos temperaturas de la cámara de germinación. Con respecto a la semilla almacenada en refrigeración, la semilla escarificada tuvo una ventaja de germinar de 11,9 a 1 sobre la no escarificada. En el caso de la temperatura de germinación, 27 °C tuvo una ventaja de 11,3 a 1 sobre 30 °C. Conclusión. La temperatura de almacenamiento y la de la cámara de germinación tuvieron influencia sobre la germinación de semillas escarificadas y no escarificadas.

Descargas

Citas

Awan, T.H., B.S. Chauhan, and P.C. Cruz. 2014. Physiological and morphological responses of Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. (Wrinkled Grass) to different nitrogen rates and rice seeding rates. PLoS One 9(6):e98255. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098255

Bakar, B.H., and L.N.A. Nabi. 2003. Seed germination, seedling establishment and growth patterns of wrinklegras (Ischaemum rugosum Salisb.). Weed Biol. Manag. 3(18):8-14. doi:10.1046/j.1445-6664.2003.00075.x

Dürr, C., J.B. Dickie, X.Y. Yang, and H. Pritchard. 2015. Ranges of critical temperature and water potential values for the germination of species worldwide: Contribution to a seed trait database. Agric. For. Meteorol. 200:222-232. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2014.09.024

Finch, W.E., and G. Leubner. 2006. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 171:501-523. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01787.x

Hernández, F. 2011. Evaluación de la resistencia de poblaciones de Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. a bispiribac sodio en lotes arroceros de la zona del Ariari, Meta. Tesis Msc., Universidad Nacional de Colombia, COL.

Herrera, J., y R. Alizaga. 1995. Efecto de la temperatura sobre la germinación de la semilla de china (Impatiens balsamina). Agron. Costarricense 19(1):79-84.

Jarma, A., J. Arbelaez, y J. Clavijo. 2007. Germinación de Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. en respuesta a estímulos ambientales y químicos. Rev. Temas Agrarios 12(2):31-41. doi:10.21897/rta.v12i2.1198

Konate, G., O. Traoré, and M.M. Coulibaly. 1997. Characterization of rice yellow mottle virus isolates in Sudano-Sahelian areas. Arch. Virol. 142:1117-1124. doi:10.1007/s007050050146

Labrada, R. (ed.). 2004. Manejo de malezas para países en desarrollo. Estudio FAO producción y protección vegetal 120. Addendum 1. FAO, Roma, ITA.

Labrada, R., J.C. Caseley, y C. Parker. 1996. Manejo de malezas para países en desarrollo. Estudio FAO producción y protección vegetal 120. FAO, Roma, ITA.

Marenco, R.A., and R.V. Santos. 1999. Wrinkledgrass and rice intra and interspecific competition. Rev. Bras. Fisiol. Veg. 11(2):107-111.

Moreira, N., y J. Nakagawa. 1988. Semillas. Ciencia, tecnología y producción. Agropecuaria Hemisferio Sur, Montevideo, URY.

Murphey, M., K. Kovach, T. Elnacash, H. He, L. Bentsink, and K. Donohue. 2015. DOG1-imposed dormancy mediates germination responses to temperature cues. Environ. Exp. Bot. 112:33-43. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.11.013

Ortiz, A., S. Blanco, G. Arana, L. López, S. Torres, Y. Quintana, P. Pérez, C. Zambrano, y A. Fischer. 2013. Estado actual de la resistencia de Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. al herbicida bispiribac-sodio en Venezuela. Bioagro 25(2):79-89.

Pabón, R. 1983. Algunos aspectos biológicos de la maleza falsa caminadora (Ischaemum rugosum). COMALFI 84(34):3-47.

Pérez, F. 2003. Germinación y dormición de semillas. En: Consejería de Medio Ambiente, editor, Material vegetal de reproducción: manejo, conservación y tratamiento. Junta de Andalucía, Andalucía, ESP. p. 177-200.

Richards, G. 2015. Especies invasoras compendio. CABI, Wallingford, GBR. www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/28909 (consultado 5 de mar del 2015).

SAG (Secretaria de Agricultura y Ganadería). 2003. Manual técnico para el cultivo de arroz (Oryza sativa). SAG, Comayagua, HON.

Vallejos, E., y A. Soto. 1995. Influencia del estado de desarrollo del arroz sobre su tolerancia al fenoxaprop-etilo y sobre la interferencia de la maleza Ischaemun rugosum. Agron Costarricense 19(2):67-63.

Valverde, B. 2007. Status and management of grass weed herbicide resistance in Latin America. Weed Technol. 21:310-323. doi:10.1614/WT-06-097.1

Vargas, M. 1994. Estudio del comportamiento de semillas de la maleza “La Falsa Caminadora” (Ischaemum rugosum) bajo diferentes condiciones de siembra, temperatura y humedad. BOLTEC 27(1):52-58.

Archivos adicionales

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

1. Política propuesta para revistas de acceso abierto

Los autores/as que publiquen en esta revista aceptan las siguientes condiciones:

- Los autores/as conservan los derechos morales de autor y ceden a la revista el derecho de la primera publicación, con el trabajo registrado con la licencia de atribución, no comercial y sin obra derivada de Creative Commons, que permite a terceros utilizar lo publicado siempre que mencionen la autoría del trabajo y a la primera publicación en esta revista, no se puede hacer uso de la obra con propósitos comerciales y no se puede utilizar las publicaciones para remezclar, transformar o crear otra obra.

- Los autores/as pueden realizar otros acuerdos contractuales independientes y adicionales para la distribución no exclusiva de la versión del artículo publicado en esta revista (p. ej., incluirlo en un repositorio institucional o publicarlo en un libro) siempre que indiquen claramente que el trabajo se publicó por primera vez en esta revista.

- Se permite y recomienda a los autores/as a publicar su trabajo en Internet (por ejemplo en páginas institucionales o personales) antes y durante el proceso de revisión y publicación, ya que puede conducir a intercambios productivos y a una mayor y más rápida difusión del trabajo publicado (vea The Effect of Open Access).